I'm looking forward to returning to the Explorers Club. The club itself is a great place to explore, filled with memorabilia from countless expeditions to the far reaches of the Earth and also outer space. Noteworthy past members include Robert Peary (of North Pole fame), Roy Chapman Andrews (arguably the model for Indiana Jones), Roald Amundsen (of South Pole fame), Theodore Roosevelt, Edmund Hillary, and astronaut Neil Armstrong. Astronauts Buzz Aldrin and John Glenn are current members.

I'll be talking about my own expeditions through the mountains of northwestern Mexico in search of the giant Imperial Woodpecker—largest woodpecker that ever lived and perhaps the rarest bird on the planet. It hasn't had a documented sighting since 1956, and yet stories persist among mountain villagers that a handful of them yet live on. My goal was to find out if the rumors were true, and beyond that, to talk with people who knew this species intimately, and try to find out why its numbers plummeted so precipitously in the late 1940s and early '50s.

The Explorers Club is at 46 E. 70th Street, New York, NY. The reception begins at 6:00 p.m. and my talk at 7:00. For full details, call (212) 628-8383, send email to reservations@explorers.org, or click on this link. Hope to see you there.

Friday, November 1, 2013

Monday, October 21, 2013

Next stop, the Explorers Club—November 4

I'll be taking my Imperial Woodpecker talk to the Explorers Club in New York City on Monday night, November 4. There's a reception at 6:00, followed by my talk at 7:00. Hope all my New York friends can make it. Here's a link for more information.

In the vast mountain pine forests of Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental lived a bird like no other—a spectacular giant woodpecker, two feet in length, largest of its clan that ever lived. With the deepest black plumage and brilliant, snow-white feathers that show as a white shield on its back, the Imperial is the closest relative of America's famed Ivory-billed Woodpecker. The last documented sighting of an Imperial Woodpecker took place in 1956, and yet rumors still persist among the mountain villagers that this bird still lives on in the remotest reaches of this mighty mountain range.

To find out if the rumors could possibly be true, author Tim Gallagher set out on a harrowing journey through the high country of the Sierra Madre, a vast, lawless region—now the epicenter of illegal drug growing in Mexico. Join Tim for a fascinating evening as he shares his adventures in search of this enigmatic ghost bird.

Tim Gallagher (FN '06) is an award-winning author, wildlife photographer, and magazine editor. He received the Explorers Club Presidents Award for Conservation in 2006. He is currently editor-in-chief of Living Bird, the flagship publication of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Tim's lifelong interest in wilderness exploration has taken him twice to northern Greenland, where he made two open-boat voyages up the coast to study nesting seabirds and falcons, and to the hinterlands of Iceland, where he climbed lofty cliffs to learn more about the spectacular Gyrfalcon, the world's largest falcon. In addition to his latest book, Imperial Dreams, Tim is the author of Falcon Fever, The Grail Bird, Parts Unknown, and Wild Bird Photography.

To make a reservation, please call (212) 628-8383 or send an email to: reservations@explorers.org

In the vast mountain pine forests of Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental lived a bird like no other—a spectacular giant woodpecker, two feet in length, largest of its clan that ever lived. With the deepest black plumage and brilliant, snow-white feathers that show as a white shield on its back, the Imperial is the closest relative of America's famed Ivory-billed Woodpecker. The last documented sighting of an Imperial Woodpecker took place in 1956, and yet rumors still persist among the mountain villagers that this bird still lives on in the remotest reaches of this mighty mountain range.

To find out if the rumors could possibly be true, author Tim Gallagher set out on a harrowing journey through the high country of the Sierra Madre, a vast, lawless region—now the epicenter of illegal drug growing in Mexico. Join Tim for a fascinating evening as he shares his adventures in search of this enigmatic ghost bird.

Tim Gallagher (FN '06) is an award-winning author, wildlife photographer, and magazine editor. He received the Explorers Club Presidents Award for Conservation in 2006. He is currently editor-in-chief of Living Bird, the flagship publication of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Tim's lifelong interest in wilderness exploration has taken him twice to northern Greenland, where he made two open-boat voyages up the coast to study nesting seabirds and falcons, and to the hinterlands of Iceland, where he climbed lofty cliffs to learn more about the spectacular Gyrfalcon, the world's largest falcon. In addition to his latest book, Imperial Dreams, Tim is the author of Falcon Fever, The Grail Bird, Parts Unknown, and Wild Bird Photography.

To make a reservation, please call (212) 628-8383 or send an email to: reservations@explorers.org

Sunday, October 13, 2013

Steve Bodio Reviews Imperial Dreams

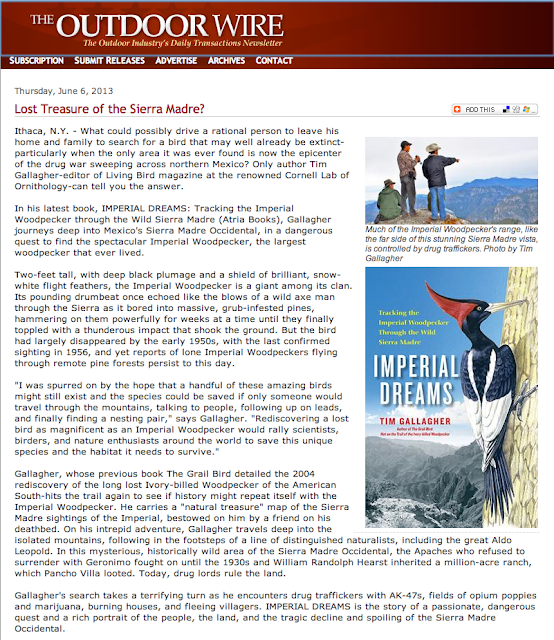

(Photo by Tim Gallagher)

Imperial Dreams by Tim Gallagher is a natural history of the world’s most spectacular woodpecker and a mystery: a forensic inquiry into what, despite the narrator’s hopes, looks like the death of a species. It starts as a lighthearted adventure and becomes a tragedy and a tale of terror. It may be Gallagher’s best book yet, one to excite adventure travelers who might never pick up a “bird book,” while telling an unforgettable tale of loss.

Several years ago, Gallagher was one of the rediscoverers of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. His success led him to think about its relative, the legendary Imperial Woodpecker (or Pitoreal ) of Mexico. I do not use “legendary” lightly; although the ivory-bill was the largest woodpecker in the United States, the imperial was the largest that ever lived. The raven-sized male, with its red Woody Woodpecker crest, looked like a huge exaggeration of the ivory-bill. But the female had a unique forward-curving black curl recognizable even in pre-Columbian petroglyphs. They knocked such large chunks of bark off dying trees that their sign was unmistakable. Their home was the cold montane pine forests of the Sierra Madre, with grizzly bear, wolf, jaguar, trout, and Thick-billed Parrot, all vanished or vanishing. Though they had been seen on occasion into the 1970s, there were few credible recent reports. Their forests had been cut over by loggers, and were now the virtual property of drug traffickers— the narcotraficantes—whose reign of terror discouraged all outsiders.

Tim Gallagher was born in England, raised in southern California, and is a longtime resident of Ithaca, New York. He is tall, thin, and gray-haired. For such a person to wander the Sierra Madre with pictures of woodpeckers, asking nervous peasants about them, takes either extreme courage or foolhardiness. But that’s just what he did.

The final of his five expeditions started optimistically in Durango, but before they left for the mountains they were “befriended” by an obvious drug dealer, and abandoned by one of the ornithologists who had agreed to accompany them. Despite such omens, they continued.

Tim often digresses in the book to explore the not-too-distant past of the Sierra Madre, telling stories of pioneer anthropologist Carl Lumholtz, and of famed ecologist and essayist Aldo Leopold, who wanted to establish the largest park in Mexico there. He reminds us that the Apaches held out in the Sierra, with bounties on their scalps, until the 1930s. They meet many decent people, though most are wary of these strange outsiders. They see opium poppies, and are warned off more than one trail. The country has been logged, and the forest is second or third growth, with ground plants eaten to stubble by goats and burros. They see one mesa across a chasm that looks like better habitat, but are warned that it belongs to the Zetas—a fearsome drug cartel made up of paramilitaries once part of the Mexican military—who will kill them if they enter. What they do not see is any sign of the woodpecker. They have a device that makes a double-knock sound that mimics the distinctive drumming of the pitoreal and most other woodpeckers in the Campephilus genus, but they never hear a response.

Their drive out of the mountains is a nightmare. The relatively benign drug lord who promised to meet them and accompany them—and warned them not to leave without him—does not show. Without “Carlos” and his Uzi submachine gun, they must drive, unescorted, for a long day over hideous dirt roads, at no more than five miles per hour. They ask a local village elder if it is safe, and he tells them: “Along the road, everything is quiet—the only thing that happened is that a few houses were burned down”—this since they entered, a couple of weeks earlier. They stop for snacks, and the proprietor seems nervous; later they find that a villager had been kidnapped and held for ransom there the day before.

Tim tries to be optimistic about the fate of the pitoreal, as he does about the ivory-bill. Although long-lived individuals may have survived into our time, do they have much future? The Imperial Woodpecker’s fate might seem even grimmer than the ivory-bill’s; the researchers find evidence that loggers repeatedly encouraged shooting and poisoning the bird to ensure its demise. If true, it represents a case of successful, conscious biocide; worse, one done for imaginary reasons—the destruction of trees that were already infested with beetle grubs. Tim’s excellent adventure contains a dark warning for any species that is perceived as an economic threat.

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Speaking in Texas next week

I hope all of my Texas birding friends will come to my talk about the Imperial Woodpecker next Thursday at the World Birding Center at Quinta Mazatlan in McAllen, Texas. The talk begins at 6:00 p.m. on October 17. For more information, call (956) 681-3370. A map is pasted below.

Tuesday, September 24, 2013

An upcoming talk at Montezuma Audubon in Savannah, New York.

Nature of Montezuma Lecture

Imperial Dreams: Tracking the Imperial Woodpecker Through the Wild Sierra Madre

Saturday, October 5, 2013

2:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.

In the vast mountain pine forests of Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental lived a bird like not other—a spectacular giant woodpecker, two feet in length, largest of its clan that ever lived. With the deepest black plumage and brilliant snow-white feathers that show as a white shield on its back, the Imperial Woodpecker is the closest relative of America's famed Ivory-billed Woodpecker. The last documented sighting of an Imperial Woodpecker took place in 1956, and yet rumors still persist among the mountain villagers that this bird still lives in the remotest reaches of this mighty mountain range. Join award-winning author and wildlife photographer Tim Gallagher at the Montezuma Audubon Center (2295 State Route 89, Savannah, New York) for a fascinating program as he shares his adventures in search of this enigmatic ghost bird. Fee: $3.00/child, $5.00/ adult, and $15/family. Free for Friends of the Montezuma Wetlands Complex. Space is limited. Registration required. Call (315) 365-3588 or email montezuma@audubon.org.

Saturday, September 21, 2013

Saturday, September 14, 2013

OWAA conference keynote on Imperial Woodpecker

I gave the keynote address at the OWAA 2013 annual conference this morning at Lake Placid, New York. Of course, my talk was all about the Imperial Woodpecker.

Keynote

Imperial Dreams: Searching for the World's Rarest Bird

in the Drug-War Zone of Northern Mexico

Speaker: Tim Gallagher

Lussi Ballroom (8:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m.)

In the vast mountain pine forests of Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental lived a bird like no other—a spectacular giant woodpecker, two feet in length, largest of its clan that ever lived. The last documented slighting took place in 1956, and yet rumors still persist among the mountain villagers that the bird still lives on in the remotest reaches of this mighty mountain range—a vast, lawless region, and now the epicenter of illegal drug growing in Mexico. To find out if the rumors could possibly be true, author Tim Gallagher set out on a harrowing journey through the high country of northern Mexico. Join Tim for a fascinating program as he shares his adventures in search of this enigmatic ghost bird.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Monday, September 9, 2013

My latest radio interview . . .

I was a guest on Ray Brown's Boston-based Talkin' Birds radio show yesterday. Here's a link to a recording of the show. My interview starts 9:50 minutes into the recording.

Monday, August 26, 2013

George Plimpton and the Imperial Woodpecker

(Illustration by Don Eckelberry, from the Audubon article.)

One of my favorite popular articles about the Imperial Woodpecker was written by famed author George Plimpton for the November-December 1977 issue of Audubon. Plimpton had gone searching for the bird in Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental with his friend Victor Emanuel, the legendary birder and founder of Victor Emanuel Nature Tours. The article was titled "Un Gran Pedazo de Carne"—which literally translates "A Great Piece of Meat" and is how a man Plimpton interviewed in the Sierra Madre described an Imperial Woodpecker he had killed and eaten fourteen years earlier.

Unfortunately, Plimpton introduced some apocryphal information in this article. When he mentioned William Rhein (the man who had taken 16mm footage of a female imperial—the only photographic documentation in existence of a living Imperial Woodpecker) he misspelled his name as "Rheim." But worse, he wrote, "On Rheim's next trip into the area in 1958, he met an Indian on the trail carrying a dead imperial he had shot: that was probably one of the pair Rheim had seen in 1954. That expired bird in the Indian's hand is the last authoritative sighting [of an Imperial Woodpecker].

This information is wrong on several counts. Rhein went to Mexico not twice but three times—in 1953, '54, and '56—and never in 1958. And Rhein did not run into someone carrying a fresh-killed Imperial Woodpecker. What Plimpton may have been inaccurately reporting was something Rhein wrote in a March 1, 1962, letter to Ivory-billed Woodpecker researcher James Tanner: "In 1955 when I was unable to return to Mexico the local Indian shot the parent birds that I had localized in the previous year. When we returned in 1956 there was one lone female flying about. I obtained some poor pictures of this bird." This 1956 bird was the one that Rhein filmed and was truly the last authoritative (and only photographically documented) sighting of an Imperial Woodpecker. Plimpton repeated his error in a book review he wrote for the New York Review of Books in March 1993.

I am a great admirer of George Plimpton's writing and would not criticize him except that these errors have found their way into the scientific literature and need to be corrected. (But the Audubon article is still well worth reading.)

One of my favorite popular articles about the Imperial Woodpecker was written by famed author George Plimpton for the November-December 1977 issue of Audubon. Plimpton had gone searching for the bird in Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental with his friend Victor Emanuel, the legendary birder and founder of Victor Emanuel Nature Tours. The article was titled "Un Gran Pedazo de Carne"—which literally translates "A Great Piece of Meat" and is how a man Plimpton interviewed in the Sierra Madre described an Imperial Woodpecker he had killed and eaten fourteen years earlier.

Unfortunately, Plimpton introduced some apocryphal information in this article. When he mentioned William Rhein (the man who had taken 16mm footage of a female imperial—the only photographic documentation in existence of a living Imperial Woodpecker) he misspelled his name as "Rheim." But worse, he wrote, "On Rheim's next trip into the area in 1958, he met an Indian on the trail carrying a dead imperial he had shot: that was probably one of the pair Rheim had seen in 1954. That expired bird in the Indian's hand is the last authoritative sighting [of an Imperial Woodpecker].

This information is wrong on several counts. Rhein went to Mexico not twice but three times—in 1953, '54, and '56—and never in 1958. And Rhein did not run into someone carrying a fresh-killed Imperial Woodpecker. What Plimpton may have been inaccurately reporting was something Rhein wrote in a March 1, 1962, letter to Ivory-billed Woodpecker researcher James Tanner: "In 1955 when I was unable to return to Mexico the local Indian shot the parent birds that I had localized in the previous year. When we returned in 1956 there was one lone female flying about. I obtained some poor pictures of this bird." This 1956 bird was the one that Rhein filmed and was truly the last authoritative (and only photographically documented) sighting of an Imperial Woodpecker. Plimpton repeated his error in a book review he wrote for the New York Review of Books in March 1993.

I am a great admirer of George Plimpton's writing and would not criticize him except that these errors have found their way into the scientific literature and need to be corrected. (But the Audubon article is still well worth reading.)

Thursday, August 22, 2013

On the death of my friend and mentor, Jack Hagan

In Memoriam

John W. Hagan

(1930 – 2013)

I just heard that my old friend Jack Hagan passed

away earlier this week, on Monday, August 19. I first met Jack at a meeting of

a newly formed club, the Santa Ana Valley Falconers’ Association, when I was in

my early teens, and he became a great mentor to me in falconry as well as

in wildlife photography. The club met weekly at Jack’s home in Santa Ana,

California, and later at Jeff Sipple’s house in Cypress. Recently divorced,

Jack was a professional photographer and also a collector of various reptiles

and amphibians (which might explain the divorce). I remember he kept live

rattlesnakes in aquariums in his garage and rare turtles in his bathtub. His

house was often sweltering inside, to accommodate the tropical turtles.

Jack took some amazing photographs in the late

1940s of a Peregrine Falcon nest in Laguna Canyon. When he came back from the

Korean War, though, the nest was empty, and the peregrines never nested there

again. This was but one of the California peregrine nests he knew off that had

been abandoned during the DDT era.

Jack was in his mid-thirties when the club formed,

with thinning dark-brown hair and a pipe he puffed on constantly. He had the

most calm, unflappable nature of anyone I’ve ever met. The younger guys in the

club called him the “Old Man,” which always made him smile. He had certain

catch phrases he would use in conversation. If you asked him a complex

question, he would puff thoughtfully on his pipe and say, “This I do not know,”

but would then go on to expound in great detail his theory on the topic at hand. He

drove a classic Mercedez 300 SL sports car with gull-wing doors and usually

flew goshawks.

Jack had an extensive collection of old falconry

books, as well as some beautiful framed 19th-century falconry prints on the walls of his

house. He told me I was welcome to come over anytime and read his books, which

I often did.

Jack would later become the first president of the

California Hawking Club, which, in some ways, sprang from the ashes of the

Santa Ana Valley group, using the same logo, which artist Jeff Sipple designed.

The last time I saw Jack was in 2001 at the 30th

annual field meet of the California Hawking Club, which was held that year in Bakersfield. I had moved to Upstate New York about a decade earlier and didn’t get to California much anymore. We—and several other

charter members of the club, such as Jeff Sipple, Bob Winslow, and Mike

Arnold—came to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the club’s founding.

It was great to see Jack. He hadn’t changed much. His hair had gone gray, and somewhere along the way he had given up the pipe, but he was the same affable, good-natured Jack. I will truly miss him.

It was great to see Jack. He hadn’t changed much. His hair had gone gray, and somewhere along the way he had given up the pipe, but he was the same affable, good-natured Jack. I will truly miss him.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Reviewed in The Nature Conservancy's Science Blog

Here's a new review of Imperial Dreams from Cool Green Science, The Nature Conservancy's science blog.

Thursday, July 25, 2013

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

My latest radio interview

I did a live interview yesterday on WSKG radio's weekly author program, Off the Page, discussing my search for the Imperial Woodpecker in the mountains of northwestern Mexico. Here's a link to the show's webpage, which has a tape of my interview: Off the Page/Imperial Dreams.

Saturday, June 29, 2013

Of Dodos, Darwin—and Imperial Woodpeckers

Photo: Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum

I apologize for going so long without writing a new blog post. For almost three weeks, I’ve been traveling around England, visiting friends and relatives, birding, sightseeing, and exploring various museum collections. One of my most interesting days on the entire journey was spent at the Natural History Museum at Tring—about 30 miles northwest of London—where the bird collection is housed.

What’s most remarkable about this collection is the number of type specimens, or syntypes—an individual or set of specimens upon which the scientific description and name of a new species is based—housed there. I saw the first

specimen of a California Condor, collected more than two centuries ago by

Archibald Menzies as it dined on a beached whale on the Monterey Peninsula.

Menzies was surgeon during Captain George Vancouver’s epic voyage of discovery from

1791 to 1795. I marveled at the full standing skeleton of a Dodo, and I was delighted

to see the finches and other birds collected by young Charles Darwin in the

Galapagos Islands during the voyage of the Beagle.

But for me, the most special specimens were the four Imperial

Woodpeckers once owned by famed ornithologist and bird artist John Gould. (Two

more of his Imperial Woodpecker specimens reside at the Liverpool Museum.) The

scientific world first took note of this species on August 14, 1832, when Gould

brought several specimens of this previously undescribed bird, “remarkable for

its extraordinary size,” to a meeting of the Zoological Society of London,

where they must have created quite a sensation. It was Gould who gave the bird

its regal appellation—Picus imperialis—which was later changed to Campephilus imperialis. (Another 19th-century English ornithologist, George Robert

Gray, established the genus Campephilus,

which means "lover of grubs," the primary diet of these birds, the

larvae of wood-boring beetles.) What a bird. What a discovery.

But for me, the most special specimens were the four Imperial

Woodpeckers once owned by famed ornithologist and bird artist John Gould. (Two

more of his Imperial Woodpecker specimens reside at the Liverpool Museum.) The

scientific world first took note of this species on August 14, 1832, when Gould

brought several specimens of this previously undescribed bird, “remarkable for

its extraordinary size,” to a meeting of the Zoological Society of London,

where they must have created quite a sensation. It was Gould who gave the bird

its regal appellation—Picus imperialis—which was later changed to Campephilus imperialis. (Another 19th-century English ornithologist, George Robert

Gray, established the genus Campephilus,

which means "lover of grubs," the primary diet of these birds, the

larvae of wood-boring beetles.) What a bird. What a discovery.

(Photo by Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum)

Gould was vague about where the specimens were

collected, saying they were obtained from “that little explored district of

California which borders the territory of Mexico.” Apparently, the skins were

actually collected by an Italian mining engineer named Damiano Floresi, who

collected a number of birds early in the 19th century in the Sierra Madre near Bolaños, Jalisco—a very long way from

California.

(Photo by Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum)

Robert Prys-Jones (above, holding one of Gould's Imperials), curator of birds at the museum, was kind

enough to give me a behind-the-scenes look at the collection and let me photograph

the specimens that most interested me. It was an unforgettable morning.

Thursday, June 6, 2013

Wednesday, June 5, 2013

Monday, June 3, 2013

Friday, May 24, 2013

Tuesday, May 21, 2013

Monday, May 20, 2013

Sunday, May 12, 2013

How to Paint a Pair of Imperial Woodpeckers . . .

Here's a fascinating blog post by artist Julie Zickefoose, describing the process she went through in painting an illustration of an Imperial Woodpecker pair. The illustration appeared with her review of Imperial Dreams in the weekend edition of the Wall Street Journal.

Saturday, May 11, 2013

Imperial Dreams reviewed in the Wall Street Journal

The Birder’s Holy Grail

The Imperial Woodpecker—at two feet tall, the largest woodpecker that

ever lived—has not been seen in more than half a century.

By Julie Zickefoose

Even though Tim Gallagher reported seeing

an ivory-billed woodpecker, the imperial woodpecker’s northern cousin, fly across

Arkansas’s Bayou De View in 2004 (and wrote a 2006 book, “The Grail Bird,”

about his quest), you're aware from the get-go that his hunt for the imperial

woodpecker in Mexico won't be a saga of discovery. There won’t be a photo of an

oversize, pied woodpecker on the book’s cover, just an artist's rendering.

Instead, “Imperial Dreams” is more along the lines of Peter Matthiessen’s “The

Snow Leopard.” It’s yearning, put into words and wistfully unrequited.

Sheer precipices abound in northern Mexico’s

Sierra Madre, but drug dealers known as narcotraficantes have turned

this place into a foreboding nightmare landscape. It's there, in remnant

old-growth pine savanna, that Mr. Gallagher seeks his dream bird, leaving home

and family for five expeditions through one of Earth’s most dangerous mountain

ranges. This is where Geronimo surrendered to Gen. Nelson Miles in 1886; where

Pancho Villa looted William Randolph Hearst’s ranch; where the Tarahumara

Indians, those fabled light-footed, long-distance runners, clung to their

lifestyle well into the 20th century. Today it is a barely modernized place of

adobe huts and wandering burros; the explorers’ trucks jolt along two-track

roads are faster walked than driven.

Mr. Gallagher paints vivid pictures of an

impoverished populace under the thumb of the rapacious drug lords, who log

illegally to clear patches for opium and marijuana, who kill indiscriminately

and without legal consequence to maintain their duchies. In one harrowing

passage, Mr. Gallagher and his friends ride in a narcotraficante’s pickup,

having fallen into nervous collaboration with him in their quest for access to

unlogged forest. As I read, I wondered why the author was going through it all,

and wondered again and again as he rattled his teeth in old vehicles and

collapsed from dehydration and exhaustion, or dodged thieves and druglords’

spies, always chasing an ornithological phantasm.

The imperial woodpecker, like its smaller

American cousin, the ivory-billed woodpecker, is almost certainly gone. These

majestic Mexican birds were deliberately persecuted, with loggers shooting them

and even poisoning the trees upon which they fed, under the false belief that

the imperial woodpeckers damaged valuable timber. Yet the inaccessibility of

what mature pine forest remains lures Mr. Gallagher ever onward—perhaps a pair

or two still cling to life in these high cold mountains. He seeks out village

elders who remember seeing the woodpeckers, each anecdote of their encounters

throwing a little more propellant on his all-consuming fire. Finally, he must

be content not with seeing the bird for himself but simply with speaking with

those aging eyewitnesses who knew it. As his role subtly shifts from explorer

to recorder, he loosens his obsessive determination to find the bird, relegating

himself to a reporter’s role and readying himself for an eventual escape from

an underworld of fantasy and desire.

I’m glad that there are people in this

world like Tim Gallagher: people who leave their armchairs, sweat bullets at

armed roadblocks, and eat cold sardines, beans and noodles so the rest of us can

marvel at their adventures. I’m glad that Mr. Gallagher is a wonderful

storyteller and deeply knowledgeable ornithologist, who also has the nerve of a

military commando. Every time I put this book down, I picked it up again to

take in just one more chapter, lured onward by the same tantalizing bits of

evidence that kept Mr. Gallagher going. Aghast at the risks he was taking, I

was caught by the scimitar-clawed grip of the world's largest woodpecker on his—and

my—imagination.

Monday, May 6, 2013

Speaking in Ithaca on May 15, 2013

I hope some of my Ithaca-area friends will attend my talk on Monday, May 15, at 6:00 p.m. at the Tompkins County Public Library. Copies of Imperial Dreams will be on sale at the event. Details below:

Saturday, May 4, 2013

My next Imperial Dreams reading . . .

This Sunday, May 5, at 4:30 p.m. at Buffalo Street Books, 215 North Cayuga Street, Ithaca, New York.

Friday, May 3, 2013

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Monday, April 29, 2013

Searching for a Ghost Bird

Several people have asked me about an earlier piece Science Friday did about my search for the Imperial Woodpecker. (This was before I wrote Imperial Dreams.) In case you'd like to listen to it, here's a link: Science Friday: Searching for a Ghost Bird.

Sunday, April 28, 2013

Friday, April 26, 2013

Diane Rehm Show Interview

I was interviewed about my Imperial Woodpecker searches yesterday on the Diane Rehm Show in Washington, D.C. In case you missed the live interview, here's a link to a recording of the program. Just click on "Listen" in the upper left corner: Diane Rehm Imperial Dreams interview.

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Sunday, April 21, 2013

Back to the Bayou . . .

After my Imperial Woodpecker talk at the Arkansas Literary Festival in Little Rock yesterday, I saw my old Ivory-billed Woodpecker chasing friends Bobby Harrison (center) and David Luneau (right). As soon as the event was over, Bobby and I blasted to Bayou de View in eastern Arkansas and spent the rest of the day canoeing through the swamp forest, revisiting the site where we'd seen an ivory-bill nine years ago.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)