Photo: Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum

I apologize for going so long without writing a new blog post. For almost three weeks, I’ve been traveling around England, visiting friends and relatives, birding, sightseeing, and exploring various museum collections. One of my most interesting days on the entire journey was spent at the Natural History Museum at Tring—about 30 miles northwest of London—where the bird collection is housed.

What’s most remarkable about this collection is the number of type specimens, or syntypes—an individual or set of specimens upon which the scientific description and name of a new species is based—housed there. I saw the first

specimen of a California Condor, collected more than two centuries ago by

Archibald Menzies as it dined on a beached whale on the Monterey Peninsula.

Menzies was surgeon during Captain George Vancouver’s epic voyage of discovery from

1791 to 1795. I marveled at the full standing skeleton of a Dodo, and I was delighted

to see the finches and other birds collected by young Charles Darwin in the

Galapagos Islands during the voyage of the Beagle.

But for me, the most special specimens were the four Imperial

Woodpeckers once owned by famed ornithologist and bird artist John Gould. (Two

more of his Imperial Woodpecker specimens reside at the Liverpool Museum.) The

scientific world first took note of this species on August 14, 1832, when Gould

brought several specimens of this previously undescribed bird, “remarkable for

its extraordinary size,” to a meeting of the Zoological Society of London,

where they must have created quite a sensation. It was Gould who gave the bird

its regal appellation—Picus imperialis—which was later changed to Campephilus imperialis. (Another 19th-century English ornithologist, George Robert

Gray, established the genus Campephilus,

which means "lover of grubs," the primary diet of these birds, the

larvae of wood-boring beetles.) What a bird. What a discovery.

But for me, the most special specimens were the four Imperial

Woodpeckers once owned by famed ornithologist and bird artist John Gould. (Two

more of his Imperial Woodpecker specimens reside at the Liverpool Museum.) The

scientific world first took note of this species on August 14, 1832, when Gould

brought several specimens of this previously undescribed bird, “remarkable for

its extraordinary size,” to a meeting of the Zoological Society of London,

where they must have created quite a sensation. It was Gould who gave the bird

its regal appellation—Picus imperialis—which was later changed to Campephilus imperialis. (Another 19th-century English ornithologist, George Robert

Gray, established the genus Campephilus,

which means "lover of grubs," the primary diet of these birds, the

larvae of wood-boring beetles.) What a bird. What a discovery.

(Photo by Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum)

Gould was vague about where the specimens were

collected, saying they were obtained from “that little explored district of

California which borders the territory of Mexico.” Apparently, the skins were

actually collected by an Italian mining engineer named Damiano Floresi, who

collected a number of birds early in the 19th century in the Sierra Madre near Bolaños, Jalisco—a very long way from

California.

(Photo by Tim Gallagher/Courtesy of The Natural History Museum)

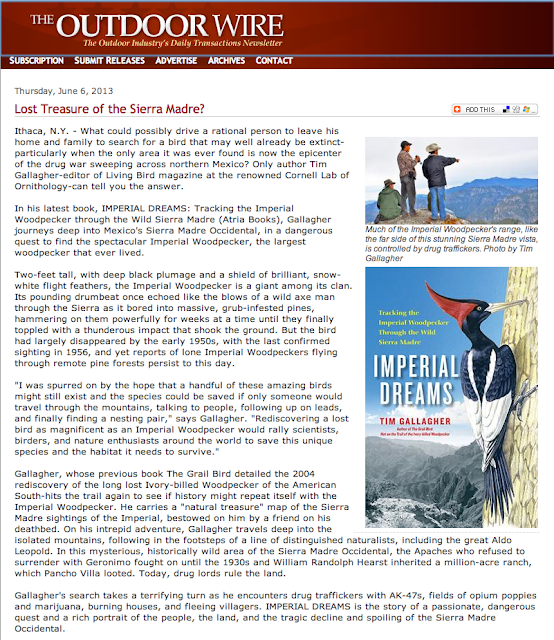

Robert Prys-Jones (above, holding one of Gould's Imperials), curator of birds at the museum, was kind

enough to give me a behind-the-scenes look at the collection and let me photograph

the specimens that most interested me. It was an unforgettable morning.