I soon joined the staff of our campus magazine at California State University: Long Beach and began searching for an interesting article topic for the next issue. This was in the 1970s, when peregrine falcon numbers had already crashed across North America and Europe as a result of DDT contamination in their environment. They were already extinct as a breeding species in the Eastern United States and were barely hanging on in the West. Researchers determined that the pesticide caused the birds to lay thin-shelled eggs, which often cracked under the weight of an incubating parent. This came as no surprise to me. The female peregrine at Morro Rock that I mentioned earlier had been found dead in her eyrie just a couple of weeks after I'd seen her. A thin-shelled egg had broken in her oviduct before she could even lay it.

Researchers were racing to find ways to stop the falcons' decline and boost their numbers. By the mid-1970s, the peregrine falcon was already on the federal endangered species list, DDT had been banned, and ornithologist (and lifelong falconer) Tom Cade had set up a massive breeding project at Cornell University and was desperately striving to reintroduce the birds in areas where their numbers had crashed. It was a daunting task for everyone involved.

Cornell professor and Peregrine Fund founder Tom Cade with Jim Weaver at Taughannock Gorge in 1975 when they tried unsuccessfully to reintroduce peregrines at the site. Photo by David Allen

I quickly realized this would be the perfect topic for my article—but what aspect should I cover? I’d heard about a group on the coast of central California that was working to save the peregrine falcons in the state. Led by raptor biologist and avid falconer Brian Walton, the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group (SCPBRG) was based in a rock quarry on the campus of the University of California: Santa Cruz.

Actor Mike Farrell from the popular television show M*A*S*H with Brian Walton at the Morro Rock eyrie.

Actor Mike Farrell from the popular television show M*A*S*H with Brian Walton at the Morro Rock eyrie.

I went up there—about a four-hour drive away—at my first opportunity and spent several days with the team, which then included bird-artist John Schmitt, falconer Merlyn Felton, veterinarian Jim Rausch, Russell Tucker, Ron Walker, and a handful of others. They had built a falcon facility in the rock quarry with breeding chambers and flight pens. Most of the falcons they were working with had been the personal birds of falconers who had donated them to the SCPBRG as potential breeders—just as falconers had done for the captive-breeding program at Cornell. None of them could bear the thought of the peregrine falcon vanishing from the Earth.

Bird artist John Schmitt with a juvenile peregrine falcon. Photo by Tim Gallagher

Bird artist John Schmitt with a juvenile peregrine falcon. Photo by Tim Gallagher

Merlyn Felton with an adult male peregrine. Photo by Tim Gallagher

Merlyn Felton with an adult male peregrine. Photo by Tim Gallagher

They were a dedicated bunch, and it was inspiring to spend time with them. One of their most important projects was attempting to ensure the success of the nesting peregrines at Morro Rock. They would remove clutches of eggs from them, substituting dummy eggs at their nest and placing their eggs in an incubator where they were in much less danger of breaking under the weight of the adults. They would later switch the dummy eggs with live young falcons, which the adults would immediately accept and begin feeding. It was all very simple and effective. Brian Walton and his wife Cheryl played a vital role in caring for these precious eggs, practically watching them round the clock to make sure the temperature and humidity were correct in the incubator. (A couple of years later Brian, still in his twenties, was diagnosed with diabetes, and in many ways, it plagued him for the rest of his life. He eventually had to have pancreas and kidney transplants. But he never stopped working hard on behalf of birds of prey, always driving himself hard to keep the project going. He died far too young in 2007 at the age of 55. I’ll always admire him.)

Falcon researcher Brian Walton and his Gyrfalcon Beulah in the 1970s. Photo by Tim Gallagher

Falcon researcher Brian Walton and his Gyrfalcon Beulah in the 1970s. Photo by Tim Gallagher

When I got back to college, my article practically wrote itself, and it was one of the main features in the magazine that semester. A few months later, the piece won a couple of major writing awards—a Hearst Foundation National Journalism Award and a California Intercollegiate Press Association Award for Best Nonfiction Magazine Article.

That clinched the deal for me. I was going to be a professional writer specializing in wildlife study and environmental issues. I switched my major and graduated with a degree in magazine journalism. But before I got my first magazine job, I headed north again and joined the crew at Santa Cruz. I couldn't think of anything more important than what they were doing, trying to save the peregrine falcon.

John Schmitt lived in a tiny travel trailer in the rock quarry, where he could keep an eye on the facility night and day. Although John was never a falconer, he had admired raptors since childhood and enjoyed taking care of the falcons. His artwork was amazing, and he completed many illustrations for the SCPBRG, The Peregrine Fund, and other groups.

Merlyn Felton (left) and John Schmitt atop Morro Rock. Photo by Glenn Stewart

Merlyn Felton (left) and John Schmitt atop Morro Rock. Photo by Glenn Stewart

Merlyn would spend a couple of months in spring and summer camping out at Morro Rock to protect the nest from intruders. (John Schmitt would later do the same for California Condors, staying for months at a time in a tiny hut in the mountains above Santa Barbara to study and help protect the birds, often going weeks without seeing another human.) They were great people, as was Danny Verrier, another falconer who played a major role at the SCPBRG.

At first, I lived in the back of my old International Travelall truck in the rock quarry, but then I moved in with Danny and his wife and kids, who were generous enough to let Merlyn and me live at their house. Famed falcon-hood-maker John Moran also soon came aboard to help with the project.

%20Brian%20Walton.jpg) With Merlyn (left) and Danny (right) in the late 1970s when we worked at the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group. Photo by Brian Walton

With Merlyn (left) and Danny (right) in the late 1970s when we worked at the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group. Photo by Brian WaltonI’ll always look back fondly on those days at Santa Cruz, spending time with a great bunch of people, helping bring back the peregrine falcon—and taking time to practice some excellent falconry. But after just a few months there, I got a job offer from an outdoor magazine based in Southern California. I was torn. I had a long talk with Brian Walton, and he strongly encouraged me to take the job. He said I could make a far more important contribution to conservation with my writing than with the work I did at the falcon project.

A young peregrine falcon at its nest in California. Photo by Tim Gallagher

A young peregrine falcon at its nest in California. Photo by Tim Gallagher

It was a tough decision, and honestly, I’m still not sure I did the right thing. But I have gotten to do a lot of interesting things in my life, traveling to faraway locations—Greenland, Iceland, Alaska, Canada, Africa, the Middle East, South America—often to help with raptor studies and write about them for books and magazines.

I finally got a chance to visit the old peregrine eyrie at Taughannock Gorge in 1990. I had flown to Ithaca, New York, to be interviewed for the position as editor-in-chief of Living Bird magazine at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—a department founded in 1915 by Arthur Allen, the very person who had taken the photograph of the eyrie that I admired so much. At the end of my interview, I asked if anyone would be willing to drive me to Taughannock Gorge, about fourteen miles away, and Scott Sutcliffe, then the Lab’s executive director, kindly volunteered.

It was eerie to be there. As I stood at the lookout, across from the falls, I could close my eyes and just imagine what it must have been like to have the loud calls of nesting peregrines echoing up and down the gorge. Maybe someday the birds will return, I thought, wistfully.

Taughannock Falls in spring. Photo by Tim Gallagher

Taughannock Falls in spring. Photo by Tim Gallagher

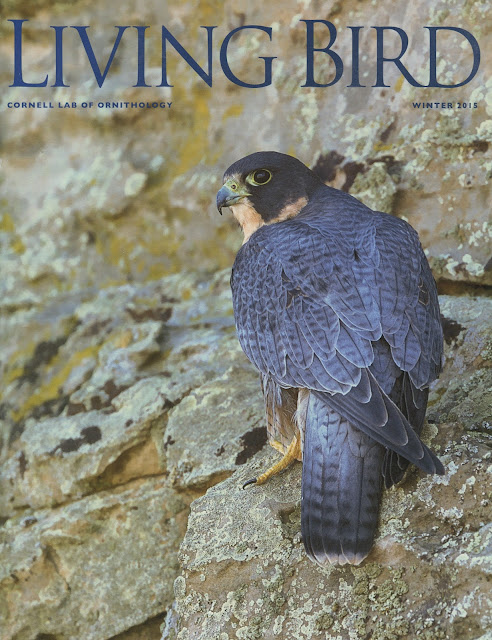

The Winter 2015 issue of Living Bird—celebrating the Cornell Lab's centennial—featured an adult peregrine falcon on the cover. Photo by Cliff Beittel

I got the job at Living Bird and worked at the Lab for more than a quarter of a century, in the meantime marrying Rachel Dickinson, a writer and Ithaca native, and raising our children with her. But it wasn’t until the spring of 2020, when the COVID pandemic kicked into high gear, that peregrine falcons finally took up residence once more at Taughannock Gorge, for the first time since 1946. And I was there to watch and document their nesting. They succeeded spectacularly, raising three young. I wrote a long feature article for Audubon about it titled “Peregrine Falcons Finally Return to Nest at Their Most Famous U.S. Eyrie.” And amazingly, the article won a national award for Best Conservation Article from the Outdoor Writers Association of America. Talk about bookends. I had written two articles, 40-plus years apart—one focused on the Morro Rock peregrines and the efforts of the SCPBRG to keep them breeding successfully; the other about the Taughannock Gorge peregrines returning after a 74-year absence—and both won major national writing awards.

Four young peregrines at the Taughannock Gorge eyrie in 2021. Photo by Tim Gallagher

I have no idea what to do for an encore, but I was happy to be invited in 2021 to take part in interviews for a documentary titled Game Hawker, about falconer Shawn Hayes, produced by Patagonia Films and directed by Josh Izenberg and Brett Marty. (I later wrote a piece for Audubon, "The Inspiring Ascent of Master Falconer Shawn Hayes.") I was flown to San Francisco and, together with Shawn and the film crew, we drove to Morro Bay to visit my other favorite peregrine eyrie. Not only was the original eyrie occupied but we saw another peregrine eyrie on a different cliff face at Morro Rock. Then, amazingly, we found out a day later that there was also a third eyrie on the seaward side of the rock that we couldn’t see. What a spectacular comeback the peregrines have made in California—and across North America.

Falconer Shawn Hayes observing one of the peregrine falcon eyries at Morro Rock. Photo by Tim Gallagher

Falconer Shawn Hayes observing one of the peregrine falcon eyries at Morro Rock. Photo by Tim Gallagher

As I write this essay, it is midwinter and I just got home from Taughannock Gorge, about twenty miles away. I didn’t see any peregrines today, just spectacular scenery. But it looks like the falcons are here to stay. They fledged three young in 2020, four in 2021, and another four in 2022. I'm hoping that the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation will soon remove the peregrine falcon from the state endangered species list, as so many other states have done. The birds are far more numerous now than they were even before the DDT era. Perhaps someday falconers in New York State will be able to fly wild peregrines again. (At the moment, we can’t even own wild peregrines legally obtained in other states.) For now, it’s just another pipe dream—like the one I had for years that peregrines would once again nest at Taughannock Gorge. We’ll see.

With daughters Clara (left) and Gwen at Taughannock Falls. Photo by Rachel Dickinson

With daughters Clara (left) and Gwen at Taughannock Falls. Photo by Rachel Dickinson

%20Brian%20Walton.jpg)