Thursday, September 21, 2023

Remembering Bryan VanCampen

Monday, September 4, 2023

Falling

I was a sky diver once. I flew to a great altitude in a small plane, crawled out on the wing, and dropped off the edge into an unknown abyss. But I wasn’t one of those fancy skydivers with all the latest gear. I picked up a cheap World War II parachute—the kind people use as a drop cloth or vehicle cover—then went looking for someone with a plane to take me up. I didn’t have a helmet or a skydiving suit. I wore a wool hat pulled low, some goggles from a hardware store, and a Levi jacket buttoned all the way to my chin.

I was living in the high desert of California in a place that used to be a major agricultural area with alfalfa farms and ranches. But the government had come in a year or two earlier and said they wanted to build a big international airport there and everyone would have to move. They bought up thousands of acres. One day the farmers were there; the next day they were gone as though they’d been magically transported away or perhaps abducted by aliens. Except a lot of them left their dogs behind, and they would roam the desert in feral packs, devouring anything they could find, including at times each other. Arsonists torched a few of the farmhouses, giving the area a grim, post-apocalyptic vibe.

I’d heard about a pilot name Corey who lived somewhere in the desert. Apparently, he’d sit around in front of his place, sipping on a tin cup of cheap whiskey, waiting for people to ask him to take them up in his plane and charging them a few bucks. He didn’t get many takers. Someone told me if I wanted to take a flight with him, I should do it early, before he’d had time to drink much, and to be sure to smell his breath. I went looking for him one afternoon, with my parachute and other gear loaded in the back of my old ’51 Chevy panel truck.

Corey’s place was just off a paved road with a small parking area and a dirt landing strip next to the shack where he lived. A peeling sign said, “Corey Air: Crop-Dusting, Charters, and Sight-Sightseeing Flights.” At one time, he had a twin-engine Cessna and flew businessmen to Los Angeles and other coastal cities for meetings, and he made a decent amount of money. He also had a crop-dusting plane and was renowned for his daring, often flying under powerlines at the end of the field so he could spray the pesticide or fertilizer over every inch of the crop. But it ruined his business when the farmers packed up. I suppose he could have gone further afield, looking for new customers, but most farms already employed pilots who’d been working for them for years. He eventually sold off both planes to get by. Now all he had was an aging biplane with two open cockpits, like something from World War I.

Corey was sitting on a folding chair in the shadow of his biplane when I pulled up. I rolled down my window and shouted: “Say, how much would you charge to take me up in your plane so I can go skydiving?” He’d been napping and woke with a start, almost falling from his chair. His skin looked parched and wrinkled, and he had shaggy gray hair, tattooed arms, and a grizzled face. His hands were greasy like he’d just been working on an engine.

“You want what?” he barked, annoyed at being woken up.

“To go skydiving. You know, I need someone to fly me up high so I can parachute down.”

He rolled his eyes and exhaled loudly. “Why the hell would you want to do that?”

“I don’t know. It’s just something I’ve always wanted to try. I went out and bought a parachute, and I’m all set to go.”

He shrugged. “Twenty bucks?”

And that was it. Ten minutes later, I was ready—wool hat pulled low with goggles in place; Levi jacket buttoned up; and parachute strapped securely in place. But the parachute was so big and awkward, I couldn’t get all the way down into the seat. So, I just put my legs in the cockpit and sat on the back of the seat, trying my best to hold onto to rim of the cockpit. Of course, I couldn’t use the seatbelt. But I figured I wouldn’t be sitting there for long.

The flight was more terrifying than anything I’d ever done before. The loudness of the engine; the shuddering vibration that rumbled through the plane; and the wind blowing hard against me as the plane raced down the runway and then rose above the desert. It was all I could do to keep from falling out and plunging downward before we’d even reached an altitude where my parachute could save me. I have no idea how high we were flying, but we passed through the clouds and eventually went well above them.

Corey finally slapped his hand loudly on the fuselage of the plane and pointed down to let me know it was time to jump. I was shaking violently as I crawled out on the wing, clinging to the struts. But I just couldn’t do it. I was paralyzed with dread. I wanted to wave at Corey to signal that I wanted to get back in the plane and not jump today, but my hands were locked in a death grip on the struts.

Corey kept pounding his fist angrily and pointing downward. Then he started making the plane bank sharply to the left and then to the right, again and again, ever more violently. I finally lost my grip, smashing my head on the wing as I was flung out into the open sky—falling…but not falling. I felt weightless, hanging in the air, far above the land. And it seemed it would go on forever—the wind whooshing around me, holding me, supporting me like a hawk soaring high overhead, barely a speck in an autumn sky. I closed my eyes and the most euphoric feeling washed over me, sheer ecstasy. I didn’t want it to end, not for anything. Then I think I passed out. For seconds? Minutes? I have no idea how much time elapsed. But then the sun burst through the clouds and the light flashed sharply in my eyes, snapping me from my trance. I instantly pulled the ripcord, but I was so close to the ground—maybe just a few hundred feet up—and still falling too fast despite the parachute. I had no control.

I could see the charred ruins of an old farmhouse below me with a row of tall trees growing along a dirt road leading away from it, and I was heading straight for them, probably falling forty miles an hour or more. I crashed hard into the top of one of the trees. It broke my fall, but I went all the way through it and bounced off the ground, twisting my ankle, then shot back up and was left dangling ten feet up in the tree. I had a folding knife in a leather snap sheath on my belt, which I pulled out and hacked through the parachute cords. As I fell to the ground, I threw the knife away so I wouldn’t end up stabbing myself. And then I just sat on the ground there, wondering how the hell I was going to get out of this mess.

I had no idea where I was, and I hadn’t made any kind of arrangements with Corey to pick me up. This was in the 1970s, long before cellphones, so I couldn’t call anyone. My mouth was parched and filled with the bitter taste of adrenaline. I needed to get my bearings somehow. It was already late afternoon and would be getting dark in a couple of hours. I limped to the farmhouse, hoping to find something useful—like a well or a water pump that worked. I was so thirsty. But there was only burned-over rubble. I did find a stout branch nearby to use as a walking stick. My ankle was swollen and painful.

I always kept a large canteen of water in my truck for desert emergencies, and I knew I had to get there as soon as possible. But which way should I go? The outline of some familiar hills in the distance and the direction of the setting sun provided some clues, but I knew it was a gamble.

I thought about walking down the farm’s dirt road, figuring it would reach a highway at some point, but it was leading in the wrong direction. To get to my car quickly, I would have to hike overland, probably going through washes and over windblown dunes in some places. When I finally got the direction fixed in my mind, I headed out, walking as briskly as possible despite my sore ankle.

I’d probably only gone two miles by the time it started getting dark. I had no idea how many more miles I had to go—maybe a dozen? And I knew I could easily miss the place in the dark. My mouth was already so parched? I wondered if I might die out there.

Then a strong wind came up, swirling sand all around me. I pulled out my old blue bandana and tied it over my mouth and nose, then I put on my goggles to keep the sand out of my eyes and trudged onward. The moon was beginning to rise, but I couldn’t see much. And then I heard it—the distant barks of a roving band of feral dogs getting closer and closer—and I felt a chill.

Would they attack a human? Why not? They’d been abandoned by the people who raised them; left to fend for themselves in one of the harshest environments on Earth. They were no doubt ravenously hungry. I’ve always loved dogs, but I knew that wouldn’t count for much here. I heard them barking loudly, maybe only a hundred yards away and headed straight for me. I turned up the collar on my jacket and made sure the top button was fastened securely, hoping it would make it harder for them to get at my throat if they attacked me. I reached for my knife but found the sheath was empty. Then I remembered I’d thrown the knife away while I was falling from the tree after cutting the parchute cords.

I lifted up my walking stick and held it before me as the dogs emerged from the swirling dust, their eyes and teeth glistening in the moonlight as they growled and snarled all around me. I knew most of them were just pack followers and would just circle me until I fell or a more aggressive dog took me down.

And then I saw him—a massive German shepherd, obviously the alpha dog. He came lunging at me, leaping upward. I leaned into his attack, smacking him on the side of the head with my stout walking stick, like a fencer parrying a sword, while the other dogs danced around my feet behind me, snapping at my heels. I knew if I stumbled and fell, it was all over. He came back at me, and I knocked him down again, always instantly holding the stick back up in front of me like a spear. It was so lucky that the branch I’d picked up was so big and sturdy. I don’t even want to think about what would have happened if it had broken.

I growled and yelled and cussed at them to show I was tough and would never give up. But really, I wasn’t sure how long I could keep going. I only knew that if I wanted to survive the night, I had to keep fighting back. I don’t even remember how long this went on. It had to be hours as I trudged miles across the desert, with dogs snapping at me and a frustrated German shepherd attacking again and again and again.

Was this all really happening? Or was this entire day with the skydiving and the wild dogs just some grim fantasy? Would I wake up in my bed in a few minutes, trembling and drenched in sweat? If only.

At some point, the winds died down and a full moon shone over the desert, illuminating my way forward. And the dogs started easing up on their attacks. Most of them had finally lost interest and drifted away. The German shepherd was still there, though he wasn’t attacking anymore. I sensed his presence even when I couldn’t see him. It was like we’d fought each other to a standstill and now were bonded in some way.

I saw the glint of metal up ahead in the moonlight and knew it was my truck. Though the inside of my mouth was dry as leather, I was sure I was going to make it, and the thought made me giddy. When I finally reached the truck and got out my canteen, I guzzled endlessly. It was the best drink I’d had in my entire life. Then I crawled inside and fell asleep.

I woke up at dawn an hour or two later, hungry and shivering from the cold. I was parked about a hundred feet from Corey’s shack and was tempted to go pound on his door and chew him out about what he did to me on the flight the day before, but I didn’t bother. I just bundled up in my blanket and sat sipping water from my canteen.

Then I saw the German shepherd again, hunting small rodents in some brush along the dirt road. And he was beautiful—so light on his feet. It was like watching a fox or a coyote in action. He would leap into a patch of cover, jump straight up in the air, then come down snapping at mice or whatever else he flushed.

I started my truck, drove closer, and sat watching him for nearly an hour. He didn’t seem to mind. I wondered how someone could have just abandoned him like that. Why didn’t these people at least drop their dogs off at the SPCA or something? How hard is that?

I looked around inside the truck to see if I had anything I could give him. I found a takeout bag with a few tortilla chips left in a little cardboard dish. I stepped outside and whistled. He froze and was wary, but I set the dish down, and he walked cautiously over to me. He sniffed at the chips for a minute, then wolfed them down. I poured some water from my canteen into the dish. He drank it all, so I gave him more. We were only three feet apart. I finally held my hand out to him with my palm up. He carefully sniffed at it as we stared into each other’s eyes. He had many scars on his head from the many fights he’d no doubt had as he struggled to survive, but his eyes were surprisingly gentle.

I walked behind my panel truck and started to open the back door. I had an overwhelming urge to take him home with me. Although I knew he had wanted to kill me just a few hours earlier, I sensed that our conflict was over and we would be great companions for the rest of our time together. But I paused and then finally stepped away from the door.

I sometimes feel sad about that and wonder how our lives might have been changed for the better if I had taken him home with me. I drove away across the desert without looking back. I never saw the dog or Corey again—and in the end, the giant international airport project that had caused all the problems petered out and it was never built.

Monday, February 27, 2023

Once Upon a Time in an Arkansas Bayou

Today marks a special anniversary for me. It was exactly nineteen years ago on February 27, 2004, that Bobby Harrison and I saw an unmistakeable Ivory-billed Woodpecker fly across the water barely 70 feet in front of our canoe and swing up to land on the trunk of a tupelo. It's a moment I'll never forget. We both yelled "Ivory-bill!" and, of course, spooked the bird, which flew a short distance to another tree and quickly hitched around to the other side of the trunk. We frantically paddled to the edge of the water, abandoned our canoe, and went off scrambling through mud and over fallen tree trunks as the huge woodpecker flew from tree to tree, tantalizingly close and yet so out of reach. Bobby had been searching for Ivory-bills for more than 30 years. He broke down and wept after our sighting, saying, "I saw an Ivory-bill...I saw an Ivory-bill..." I just stood in stunned silence.

Until that moment, I had been somewhat agnostic about whether the Ivory-billed Woodpecker still existed. There were strong points on both sides of the argument. But regardless, I felt it was vitally important to locate people who had memories of this bird and to interview them as soon as possible. Many of the people I interviewed in the beginning were in their 90s, and I knew they wouldn't be around much longer. If the Ivory-bill truly was extinct, these people were our last connection with the species, so I reasoned that we better ask any questions we have about the bird right now.

But in the course of my research, I found seemingly believable people who'd had much more recent sightings than that of the bird sketched by artist Don Eckelberry in Louisiana's Singer Tract in 1944. Some of them had purportedly been seen in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s by various hunters and others who knew the area and its wildlife well and seemed believable. Bobby and I started going together to check out the areas where the sightings took place. All too often, the areas had been destroyed to make way for agriculture and various other developments. But sometimes the places still looked great. The only problem was it had been so long since these sightings took place.

Then it happened. A kayaker, Gene Sparling, saw a large woodpecker in a bayou in eastern Arkansas and posted a description on a canoe club list-serv. We tracked Gene down and spoke on the phone with him just four days after his sighting. Bobby and I dropped everything and headed to Arkansas a few days later to spend a week floating the bayou with Gene.

Shortly after 1:00 in the afternoon—while Gene was up ahead, half a mile or so away—the bird flew across in front of us and changed our lives forever.

We went through every emotion imaginable before Gene came back and found us babbling barely coherently about the bird we'd seen. "Welcome to the Sasquatch Club," he said, and we all laughed our heads off.

If you'd like to read more about our Ivory-billed Woodpecker searches in 2004 and 2005, here's a link to "The Best Kept Secret"—an article my wife, Rachel Dickinson, wrote for Audubon fourteen months after our sighting. Or you could read my book, The Grail Bird.

As many of you know, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has proposed declaring the Ivory-billed Woodpecker extinct and removing it from the Endangered Species List. In response, I wrote an opinion piece for Audubon titled "Is it Really Time to Write the Ivory-billed Woodpecker's Epitaph?" At the moment, the final decision is still pending—and frankly, I strongly hope they decide against it.

Friday, February 10, 2023

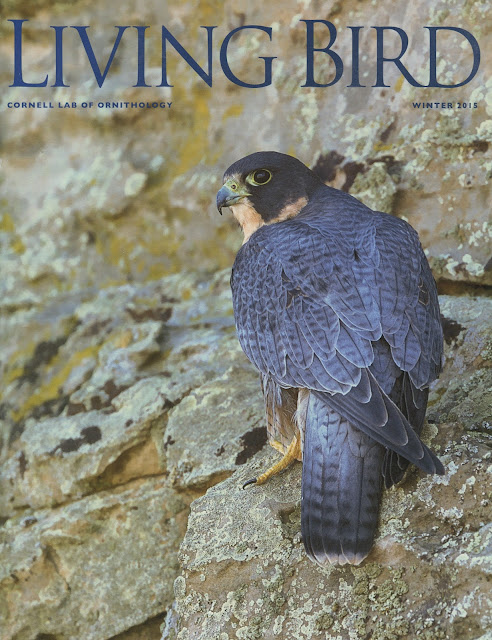

Bookends: A Tale of Two Peregrine Falcon Eyries

I soon joined the staff of our campus magazine at California State University: Long Beach and began searching for an interesting article topic for the next issue. This was in the 1970s, when peregrine falcon numbers had already crashed across North America and Europe as a result of DDT contamination in their environment. They were already extinct as a breeding species in the Eastern United States and were barely hanging on in the West. Researchers determined that the pesticide caused the birds to lay thin-shelled eggs, which often cracked under the weight of an incubating parent. This came as no surprise to me. The female peregrine at Morro Rock that I mentioned earlier had been found dead in her eyrie just a couple of weeks after I'd seen her. A thin-shelled egg had broken in her oviduct before she could even lay it.

Researchers were racing to find ways to stop the falcons' decline and boost their numbers. By the mid-1970s, the peregrine falcon was already on the federal endangered species list, DDT had been banned, and ornithologist (and lifelong falconer) Tom Cade had set up a massive breeding project at Cornell University and was desperately striving to reintroduce the birds in areas where their numbers had crashed. It was a daunting task for everyone involved.

I quickly realized this would be the perfect topic for my article—but what aspect should I cover? I’d heard about a group on the coast of central California that was working to save the peregrine falcons in the state. Led by raptor biologist and avid falconer Brian Walton, the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group (SCPBRG) was based in a rock quarry on the campus of the University of California: Santa Cruz.

Actor Mike Farrell from the popular television show M*A*S*H with Brian Walton at the Morro Rock eyrie.

Actor Mike Farrell from the popular television show M*A*S*H with Brian Walton at the Morro Rock eyrie.I went up there—about a four-hour drive away—at my first opportunity and spent several days with the team, which then included bird-artist John Schmitt, falconer Merlyn Felton, veterinarian Jim Rausch, Russell Tucker, Ron Walker, and a handful of others. They had built a falcon facility in the rock quarry with breeding chambers and flight pens. Most of the falcons they were working with had been the personal birds of falconers who had donated them to the SCPBRG as potential breeders—just as falconers had done for the captive-breeding program at Cornell. None of them could bear the thought of the peregrine falcon vanishing from the Earth.

They were a dedicated bunch, and it was inspiring to spend time with them. One of their most important projects was attempting to ensure the success of the nesting peregrines at Morro Rock. They would remove clutches of eggs from them, substituting dummy eggs at their nest and placing their eggs in an incubator where they were in much less danger of breaking under the weight of the adults. They would later switch the dummy eggs with live young falcons, which the adults would immediately accept and begin feeding. It was all very simple and effective. Brian Walton and his wife Cheryl played a vital role in caring for these precious eggs, practically watching them round the clock to make sure the temperature and humidity were correct in the incubator. (A couple of years later Brian, still in his twenties, was diagnosed with diabetes, and in many ways, it plagued him for the rest of his life. He eventually had to have pancreas and kidney transplants. But he never stopped working hard on behalf of birds of prey, always driving himself hard to keep the project going. He died far too young in 2007 at the age of 55. I’ll always admire him.)

When I got back to college, my article practically wrote itself, and it was one of the main features in the magazine that semester. A few months later, the piece won a couple of major writing awards—a Hearst Foundation National Journalism Award and a California Intercollegiate Press Association Award for Best Nonfiction Magazine Article.

That clinched the deal for me. I was going to be a professional writer specializing in wildlife study and environmental issues. I switched my major and graduated with a degree in magazine journalism. But before I got my first magazine job, I headed north again and joined the crew at Santa Cruz. I couldn't think of anything more important than what they were doing, trying to save the peregrine falcon.

John Schmitt lived in a tiny travel trailer in the rock quarry, where he could keep an eye on the facility night and day. Although John was never a falconer, he had admired raptors since childhood and enjoyed taking care of the falcons. His artwork was amazing, and he completed many illustrations for the SCPBRG, The Peregrine Fund, and other groups.

Merlyn would spend a couple of months in spring and summer camping out at Morro Rock to protect the nest from intruders. (John Schmitt would later do the same for California Condors, staying for months at a time in a tiny hut in the mountains above Santa Barbara to study and help protect the birds, often going weeks without seeing another human.) They were great people, as was Danny Verrier, another falconer who played a major role at the SCPBRG.

At first, I lived in the back of my old International Travelall truck in the rock quarry, but then I moved in with Danny and his wife and kids, who were generous enough to let Merlyn and me live at their house. Famed falcon-hood-maker John Moran also soon came aboard to help with the project.

%20Brian%20Walton.jpg) With Merlyn (left) and Danny (right) in the late 1970s when we worked at the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group. Photo by Brian Walton

With Merlyn (left) and Danny (right) in the late 1970s when we worked at the Santa Cruz Predatory Bird Research Group. Photo by Brian WaltonI’ll always look back fondly on those days at Santa Cruz, spending time with a great bunch of people, helping bring back the peregrine falcon—and taking time to practice some excellent falconry. But after just a few months there, I got a job offer from an outdoor magazine based in Southern California. I was torn. I had a long talk with Brian Walton, and he strongly encouraged me to take the job. He said I could make a far more important contribution to conservation with my writing than with the work I did at the falcon project.

It was a tough decision, and honestly, I’m still not sure I did the right thing. But I have gotten to do a lot of interesting things in my life, traveling to faraway locations—Greenland, Iceland, Alaska, Canada, Africa, the Middle East, South America—often to help with raptor studies and write about them for books and magazines.

I finally got a chance to visit the old peregrine eyrie at Taughannock Gorge in 1990. I had flown to Ithaca, New York, to be interviewed for the position as editor-in-chief of Living Bird magazine at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology—a department founded in 1915 by Arthur Allen, the very person who had taken the photograph of the eyrie that I admired so much. At the end of my interview, I asked if anyone would be willing to drive me to Taughannock Gorge, about fourteen miles away, and Scott Sutcliffe, then the Lab’s executive director, kindly volunteered.

It was eerie to be there. As I stood at the lookout, across from the falls, I could close my eyes and just imagine what it must have been like to have the loud calls of nesting peregrines echoing up and down the gorge. Maybe someday the birds will return, I thought, wistfully.

I got the job at Living Bird and worked at the Lab for more than a quarter of a century, in the meantime marrying Rachel Dickinson, a writer and Ithaca native, and raising our children with her. But it wasn’t until the spring of 2020, when the COVID pandemic kicked into high gear, that peregrine falcons finally took up residence once more at Taughannock Gorge, for the first time since 1946. And I was there to watch and document their nesting. They succeeded spectacularly, raising three young. I wrote a long feature article for Audubon about it titled “Peregrine Falcons Finally Return to Nest at Their Most Famous U.S. Eyrie.” And amazingly, the article won a national award for Best Conservation Article from the Outdoor Writers Association of America. Talk about bookends. I had written two articles, 40-plus years apart—one focused on the Morro Rock peregrines and the efforts of the SCPBRG to keep them breeding successfully; the other about the Taughannock Gorge peregrines returning after a 74-year absence—and both won major national writing awards.

I have no idea what to do for an encore, but I was happy to be invited in 2021 to take part in interviews for a documentary titled Game Hawker, about falconer Shawn Hayes, produced by Patagonia Films and directed by Josh Izenberg and Brett Marty. (I later wrote a piece for Audubon, "The Inspiring Ascent of Master Falconer Shawn Hayes.") I was flown to San Francisco and, together with Shawn and the film crew, we drove to Morro Bay to visit my other favorite peregrine eyrie. Not only was the original eyrie occupied but we saw another peregrine eyrie on a different cliff face at Morro Rock. Then, amazingly, we found out a day later that there was also a third eyrie on the seaward side of the rock that we couldn’t see. What a spectacular comeback the peregrines have made in California—and across North America.

Falconer Shawn Hayes observing one of the peregrine falcon eyries at Morro Rock. Photo by Tim Gallagher

Falconer Shawn Hayes observing one of the peregrine falcon eyries at Morro Rock. Photo by Tim GallagherAs I write this essay, it is midwinter and I just got home from Taughannock Gorge, about twenty miles away. I didn’t see any peregrines today, just spectacular scenery. But it looks like the falcons are here to stay. They fledged three young in 2020, four in 2021, and another four in 2022. I'm hoping that the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation will soon remove the peregrine falcon from the state endangered species list, as so many other states have done. The birds are far more numerous now than they were even before the DDT era. Perhaps someday falconers in New York State will be able to fly wild peregrines again. (At the moment, we can’t even own wild peregrines legally obtained in other states.) For now, it’s just another pipe dream—like the one I had for years that peregrines would once again nest at Taughannock Gorge. We’ll see.